A recurring topic in our monthly reports is the growing strain on electricity grids driven by the emergence of huge AI data centers. As discussed above, spending is accelerating, not slowing down, at least not yet. While growth will eventually moderate, in the meantime, multiple sub-cycles within the sector are being disrupted by technological and structural shifts in demand. Some cycles will fade due to declining hype, and others will become oversupplied before demand inevitably falls. We will examine several of these trends as new data centers are increasingly forced to secure their own power supply.

In our March-24 report “Roadblocks on the AI highway”, we explained that the greatest challenge to expanding data center capacity is access to power and grid connections. Our November-24 report, “The urgency to secure power”, explored future data center power options such as renewables, nuclear, natural gas, fuel cells and repurposing industrial sites or bitcoin mining facilities. Since then, most stocks in these categories have surged as urgency around AI-driven power demand has increased alongside hyperscaler investments projections.

The market is, however, ingenious. Nearly every company with any resemblance to a power-generating asset is offering their services. Hyperscalers are eager to sign contracts, often with expansion options, to secure supply in a tight market, but likely also to set up for a potential oversupply in the future. Recently, several oilfield service and equipment companies have announced fleet expansions of small gas turbines and reciprocating engines, essentially modular combustion units mounted on trailers. Gone are the days when tech companies tried to obscure their consumption of fossil fuels.

Yet, how efficient is it to run trailers with diesel and natural-gas engines to power data centers? Not very. In fact, it is incredibly inefficient, but it serves its purpose: it creates rapid supply, more optionality, and allow hyperscalers to keep building. Ultimately, we believe this is nothing more than a stopgap solution for data centers awaiting grid connection or more efficient alternatives.

From Stopgaps to Structured Power

Renewables such as solar and wind, along with large combined cycle gas turbines (CCGTs) are vital for data center buildout. Renewables offer relatively cheap and rapid power to the grid, while gas turbines provide resilience via their “spinning mass”, supporting the alternating current (AC) waveform required for grid stability.

Nevertheless, it is increasingly a requirement for data centers to “bring your own power”, but neither renewables nor large CCGTs are optimal for direct connection to a large load like a data center. However, fuel cells are well suited for this purpose: they are small, modular, and if one unit fails or need maintenance, the power supply is only marginally impacted. Fuel cells also deliver high electrical efficiency, operate quietly, and do not emit particulates. They do, however, require regular maintenance as stack efficiency declines over time, a risk that could limit their potential to serve as a permanent solution unless maintenance costs fall in line with those for renewables and gas turbines.

Bloom Energy (BE), a fund holding, is the clear market leader in solid-oxide fuel cells (SOFC), having supplied “servers” to smaller data centers for a decade. Given the acute power shortfall in parts of the US, limited viable alternatives, and the need to bring your own power, Bloom has started receiving orders from hyperscalers this year, propelling the stock nearly 500% YTD. The valuation is now clearly rich. As mentioned in last month’s report, other companies are trying to address the SOFC market, but the real challenge will be scaling in time to seize this opportunity. MOUs (memorandums of understanding) for future contracts from new entrants may materialize, but the most likely scenario is further contracts to Bloom, given its track record and expanding manufacturing base.

Not all fuel cells are the same though. There is a widespread misconception on social media that proton-exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells, like those produced by Plug Power (PLUG) or Ballard Power (BLDP), are suitable for data centers. PEM fuel cells require externally sourced, high-purity hydrogen. As we have explained many times, producing electricity from hydrogen is incredibly inefficient, but to make it worse, there is no viable infrastructure for delivering the enormous volumes required to run a data center. Supplying even a single hyperscale site would mean thousands of tanker-truck deliveries per day, obviously physically and economically impossible. In our view, PEM systems will not play a role in suppling data centers with electricity, but despite these facts, stocks in this sector have rallied hundreds of percents on hype, which will eventually end one day.

Batteries represent another key technology as data centers increasingly require onsite power and redundancy. While China still dominates the supply chain, US domestic battery supply is expanding, and battery storage was a notable beneficiary of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA). In previous monthly reports, we have covered the potential to scale Virtual Power Plants (VPPs) using aggregated batteries, a trend we expect to continue gaining importance.

Demand for power is developing so fast that both utilities and data center operators are applying an “all of the above” approach to power supply. Similarly, for on-site power generation of data centers, we believe a hybrid power stack is most likely: grid connection, medium sized gas turbines or SOFCs providing continuous on-site power, combined with batteries and supercapacitors to absorb or deliver power in milliseconds as workloads fluctuate. In effect, each site becomes a miniature utility - generating, storing, and stabilizing its own supply.

The Architectural Leap

The next shift happens inside the perimeter of the data center. NVIDIA’s recent “Data Center of the Future” whitepaper outlines an electrical redesign centered on an 800-volt direct current (DC) architecture. The traditional alternating-current (AC) hierarchy: high-voltage grid connection → step-down transformer → switchgear → UPS → server-level conversion, involves numerous conversions, each adding inefficiency and heat. Moreover, with Nvidia’s future GPUs demanding immense power, using lower-voltage AC would require power cables so thick they could not fit inside the racks of data chips.

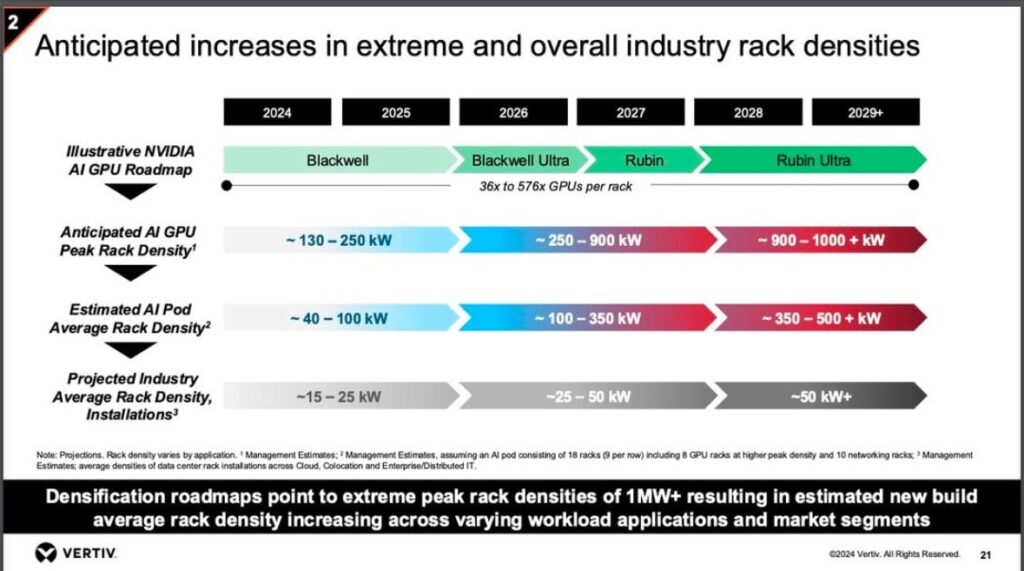

The 800-volt DC model streamlines this architecture: power supplied by on-site fuel cells, batteries or rectifiers could feed directly into a high-voltage DC bus distributing electricity across racks to the chip level. Fewer conversions mean lower losses, smaller footprints, and greater control. These advantages are critical as rack power densities approach one megawatt as demanded by Nvidia’s upcoming Rubin Ultra GPUs.

Source: Vertiv 2024

Equally important, a DC backbone integrates seamlessly with new local power assets: fuel cells, batteries, and even solar, all inherently DC devices. The data center becomes a tightly coupled microgrid with more limited demand from the grid.

Although “bring your own power” was viewed largely as an inconvenience until now, it is becoming a necessity as data centers expand and shift toward DC electrical architecture. On-site SOFCs could have a slight advantage since they produce DC power directly, while gas turbines are inherently producing AC power. Batteries, supplying DC power, will likely become more important too, rapidly responding to the wild swings in power demand from the data centers which often can shift demand from nearly nothing to 100% in milliseconds. That load volatility is not something the grid alone can handle.

The shift to “the data center of the future” will create both winners and losers: the medium-voltage transformers, switchgear and rectifiers used to convert AC-DC and to step up and down voltage might see their roles diminished or rendered obsolete in data center applications. This is one instance where a technological shift, not hype nor excess supply, can end a cycle. AI is not just consuming electricity; it is redesigning the entire system that produces and delivers it. The data center of the future will probably look less like a tenant of the grid and more like a peer utility, complete with generation, storage, and control.

For our fund, this convergence of computing and power is a key investment theme. It reaches from semiconductors and cables to turbines, renewables, fuel cells, and batteries. The short-term scramble for megawatts will eventually subside, but the structural redesign of the power system is just beginning.

While grid investments continue to benefit the most from data center expansion, new opportunities are emerging as demand structure evolves. In this vertical, winners will build for a future in which data centers not only draw power from the grid—they become integral components of it.

- Portföljförvaltare och grundare av fonden Coeli Energy Opportunities.

- Mer än 15 års erfarenhet av investeringar från både publika och private equity-sidan.

- Förvaltade fonden Coeli Energy Transition under perioden 2019 - 2023.

- Spenderade sex år på Horizon Asset i London, en marknadsneutral hedgefond.

- Började arbeta tillsammans med Vidar Kalvoy 2012.

- Fem år inom Private Equity på Morgan Stanley.

- Startade sin investeringskarriär inom tekniksektorn på Sweden Robur i Stockholm 2006.

- Utbildad Civilingenjör från Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan.

- Portföljförvaltare och grundare av Coeli Energy Opportunities-fonden.

- Förvaltat aktier inom energisektorn sedan 2006 och har mer än 20 års erfarenhet från portföljförvaltning och aktieanalys.

- Förvaltade fonden Coeli Energy Transition under perioden 2019 - 2023.

- Ansvarig för energiinvesteringarna på Horizon Asset i London under 9 år, en marknadsneutral hedgefond.

- Erfarenhet från energiinvesteringar på MKM Longboat i London och aktieanalys inom teknologisektorn i Frankfurt och Oslo.

- MBA från IESE i Barcelona och Civilekonom från Norges Handelshögskola.

- Innan han började arbeta inom finans var han löjtnant i norska marinen.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION. This is a marketing communication.

Before making any final investment decisions, please refer to the prospectus of Coeli SICAV II, its Annual Report, and the KID of the relevant Sub-Fund. Relevant information documents are available in English at coeli.com. A summary of investor rights will be available at https://coeli.com/financial-and-legal-information/. Past performance is not a guarantee of future returns. The price of the investment may go up or down and an investor may not get back the amount originally invested. Please note that the management company of the fund may decide to terminate the arrangements made for the marketing of the fund in one or multiple jurisdictions in which there exists arrangements for marketing.