This is a question with many different answers depending on who you ask. As our fund is focused on decarbonization, it is not a surprise that we believe the most important area to focus on is the energy transition. It is so important to us that we are co-operating with one of the leading Swedish universities to develop a methodology to measure the impact of avoided emissions, a relatively unexplored concept called Scope 4. More on that later.

Back to the initial question. Despite the significant increase in sustainability reporting requirements for funds, particularly in Europe, we doubt that it is much easier than in the past for investors to tell which investment funds are truly green and not. Funds are now classified into different articles: 6, 8, and 9 depending on how “sustainable” they claim to be. Although most funds truly try their best to make the planet a better place, some seem to use article 9 as a more sophisticated way to greenwash.

Let us quickly review the issue. To be an article 9 fund, the investments shall be sustainable first and performance focused second. And none of the investments should cause any harm. But what is sustainable? Apparently, most article 9 funds believe 20% or more of a company’s activities need to align to one of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Although all of the 17 SDGs are important, most of them have nothing to do with fighting climate change and some are rather vague. Also, given the 20% limit, a ”sustainable” company could theoretically have up to 80% of its revenues from activities that are not at all linked to sustainable activities, but still qualify as an investment in an article 9 fund that achieves the highest level of sustainability ranking. These funds are often referred to as ‘dark green’ funds independently of which SDGs they are focused.

Talking our own book, our fund is an article 8 fund, which means that the primary goal is to make a profit for our investors while promoting environmental and social characteristics. However, despite the fact that all our long positions are involved in clean energy production, energy efficiency or decarbonization, we decided to classify the fund as an article 8 or ‘light green’.

Moreover, if we discuss what is commonly thought of as ”green” investments, i.e. investments that improve the environment and fight climate change, there are serious limitations with the current regulatory framework. In our view, this stems partly from the initial approach within the ESG community to exclude polluters or at least only invest in companies with low emissions based on so called scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions.

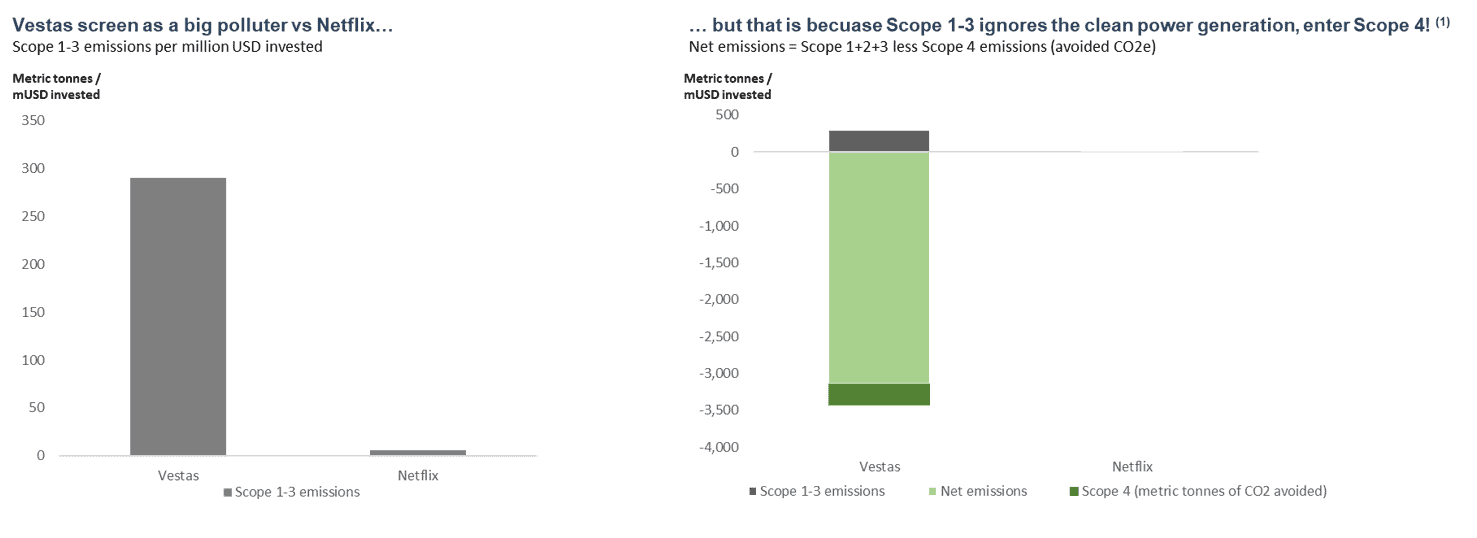

The focus on scope 1-3 emissions when it comes to climate and emissions reporting is often inadequate and sometimes directly misleading as a measure for green investments. Companies manufacturing solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, or even nuclear energy plants will inevitably have higher emissions in their operations than software companies, banks, or biotech firms. But does this operational footprint genuinely reflect their contribution, or lack thereof, fighting climate change?

This is where Scope 4 emissions become critically important as it attempts to assess the true climate impact of an investment. Scope 4 focuses on the emissions a company’s activities avoid rather than emit. For example, the manufacturing of a wind turbine involves significant emissions from producing steel, copper wires, and the foundation. However, once installed, the turbine generates clean electricity for about 30 years, essentially resulting in negative emissions over its lifetime. To illustrate this point, we have conducted our own comparison between Netflix and Vestas, demonstrating the difference in climate impact. Which stock is the greenest?

1) Avoided CO2/mUSD invested calculated as net of Scope 1-3 emissions and (capacity sold x baseline emissions x 20yr adjusted capacity factor x USD share of project (simple LCA using NREL estimates for onshore and offshore wind respectively) x 20yrs lifetime) / market cap

Admittedly, there are considerable challenges with measuring scope 4 emissions, but it does not add that much incremental complexity versus measuring scope 1-3. One major hurdle initially is that it is a relatively new concept, and the calculations lack an industry standard. However, we believe the basic concept is straightforward. For instance, OECD countries currently emit about 0.3kg of CO2 emissions per kWh of electricity production, so if a company can produce zero-emission electricity, that is the benchmark amount it avoids per kWh produced.

Nevertheless, Life Cycle Analysis and the allocation of emissions among different companies in the supply chain is one of the complicating factors. This is why we are collaborating with a Swedish university to develop a methodology that will look at the whole value chain. With this initiative we hope to scientifically explain why it is better for the climate to allocate capital to Vestas than to Netflix, which is currently not apparent when looking only at scope 1-3 emissions. This could be valuable for investors who are interested in environmentally positive allocations.

The gist is that if more investors would consider the potentially avoided emissions of their companies, more capital would be incentivized to support businesses that make a tangible difference rather than investing in companies that only have low emissions. Dark green is not always the greenest.

- Portföljförvaltare och grundare av fonden Coeli Energy Opportunities.

- Mer än 15 års erfarenhet av investeringar från både publika och private equity-sidan.

- Förvaltade fonden Coeli Energy Transition under perioden 2019 - 2023.

- Spenderade sex år på Horizon Asset i London, en marknadsneutral hedgefond.

- Började arbeta tillsammans med Vidar Kalvoy 2012.

- Fem år inom Private Equity på Morgan Stanley.

- Startade sin investeringskarriär inom tekniksektorn på Sweden Robur i Stockholm 2006.

- Utbildad Civilingenjör från Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan.

- Portföljförvaltare och grundare av Coeli Energy Opportunities-fonden.

- Förvaltat aktier inom energisektorn sedan 2006 och har mer än 20 års erfarenhet från portföljförvaltning och aktieanalys.

- Förvaltade fonden Coeli Energy Transition under perioden 2019 - 2023.

- Ansvarig för energiinvesteringarna på Horizon Asset i London under 9 år, en marknadsneutral hedgefond.

- Erfarenhet från energiinvesteringar på MKM Longboat i London och aktieanalys inom teknologisektorn i Frankfurt och Oslo.

- MBA från IESE i Barcelona och Civilekonom från Norges Handelshögskola.

- Innan han började arbeta inom finans var han löjtnant i norska marinen.

VIKTIG INFORMATION. Denna information är avsedd som marknadsföring. Fondens prospekt, faktablad och årsberättelse finns att tillgå på coeli.se och rekommenderas att läsas innan beslut att investera i den aktuella fonden. Prospektet och årsberättelsen finns på engelska och fondens faktablad finns bland annat på svenska och engelska. En sammanfattning av dina rättigheter som investerare i fonden finns tillgängligt på https://coeli.se/finansiell-och-legal-information/.

Historisk avkastning är ingen garanti för framtida avkastning. En investering i fonder kan både öka och minska i värde. Det är inte säkert att du får tillbaka det investerade kapitalet.