Logga in

In 2022 when Russia attacked Ukraine, the global economy was shaken by a severe power price shock as energy costs soared to a staggering 12% of global GDP. In the wake of diminished gas supplies from Russia, the crisis set the stage for an ongoing debate about the future of energy prices, particularly in Europe. As Europe secured its own energy supply by bidding up the global price of LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas), it left emerging markets in a difficult position.

These countries, led by China, India and Indonesia responded in a natural yet impactful way by substantially increasing coal production. This move reversed the prior trend of stable to declining global coal demand. The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) 2018 prediction of 7.6Gtpa global coal demand for 2023 fell short, as the actual figure is almost 15% higher. This surge resulted in an additional 2 billion tons of annual Green House Gas emissions, more than a 3% increase on the total annual emissions, a dire outcome for the climate.

The increased coal production in Asia is clearly one of many reasons for the sharp drop in forward power prices in Europe and Germany over the last months, which accelerated in January. This development warrants a deeper analysis.

Since mid-October, the German baseload electricity price 12- and 24-months forward are both down more than 35%, with about 70% of the decline in January. Although this is great news for European industry and the global fight against inflation, it could have a negative impact on certain subsector in the renewable energy space. An emerging worry in the financial markets is that the lower power prices will impact Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) prices as they are in effect long term contracts to purchase power.

But first, why are power prices falling? Power prices in Europe are largely a function of gas price and carbon prices, but as the latter tend to follow the gas price on the way down, the culprit is mainly the gas price. Why are both the spot and the 12-month forward gas price down by almost 50% and 24-month forward about 30% lower than in mid-October?

On the demand side, the mild winter plays a significant role combined with reduced European industrial demand, which is still lagging 15-20% below pre-energy crisis levels. Last years’ high residential energy bills also appear to have had an impact on consumer habits as demand is down more than what can be explained by the temperature. According to EMBER, an energy think tank, weather adjusted power demand in the EU 27 is down as much as 7% since 2021.

On the supply side, as described above, there has been a global increase in coal consumption facilitating the higher imports of LNG to Europe. There is also more piped gas from Norway and North Africa, while demand for gas for power production is reduced as supply of nuclear and hydro energy is up significantly since 2021/22. In addition, solar and wind capacity is added every year helping to reduce the need to burn gas for power. In total, gas demand for power production was 17% lower in H2/23 than in H2/22, according to EMBER. This is good news for Europe’s carbon footprint.

However, considering this supply/demand situation and the fact that European gas inventories were at full capacity last autumn, it is not surprising that inventories in early February is almost 70% full vs historical average in the low to mid 50% range. Moreover, assuming normal temperatures over the next months, there is a significant risk of tank tops, i.e. full storage, during the summer. In the few instances this has happened in the past, the price can briefly trade below EUR 10MWh versus almost EUR 30MWh today. Power prices correlates strongly with gas prices on the way down, so this would be a headwind for companies with limited fixed price contracts or hedges.

The above scenario is something we have been aware of for several quarters, but what has taken us by surprise is the even sharper fall in the forward power prices. The market seems to be willing to price in not only a mild winter next year, but also no significant improvement in demand for power. Demand is fundamentally difficult to forecast as it is driven by many factors, including the price level.

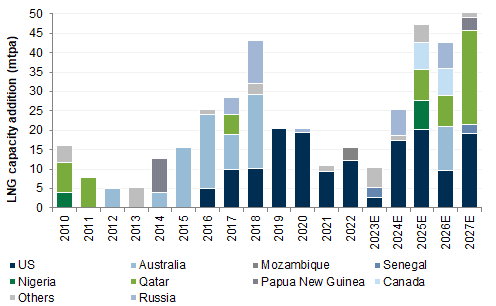

Although the supply side is also complicated, it seems likely that the global LNG markets will be well supplied the next three to four years. The two largest LNG exporters, the US and Qatar, are ramping their export capacity by 100% and 50%, respectively over the next years, see below.

Source: Goldman Sachs

The new LNG export capacity is in fact larger in size than the Russian piped gas that has been shut in. The Russian gas accounted for about 40% of Europe’s gas consumption before the war. Since European power prices are almost back to pre-war levels, the Russian gas has basically been replaced by alternative energy sources; LNG, piped gas, coal burning in Asia, new renewable energy and importantly, reduced demand from industry and households in Europe and Asia.

At first glance, it looks like we are set up for oversupply and low gas and power prices for years to come. However, it is important to have in mind that as gas prices fall, coal to gas switching will occur. Also, when power prices decline, demand will surely pick up helping to balance the market. As always in commodity markets, low prices alleviate low prices, just like the high prices of the energy crisis was cured by triggering more supply and reducing demand.

What is the impact on the PPA prices and the implication for renewable developers? PPA prices have a floor which is roughly the price at which developers make a return. This threshold is driven by capex, cost of financing and cost of capital. The PPA cannot be set below the floor as the developer would be destroying value. However, PPAs above the threshold are correlating with power prices as developers will try to maximize returns, taking advantage of arbitrage between market prices and PPA prices. On the margin, lower and most importantly declining PPA prices have, everything else equal, a negative impact on the developers. This was rapidly priced into the share prices in January, though.

Nevertheless, there are additional factors to consider. First, input costs for solar panels have halved in Europe and there is potential for lower financing costs in the near future. This could lead to attractive returns even at reduced PPA prices. Second, most renewable development projects take years from planning starts to production commences. This means basing investments decisions on volatile forward prices might be unwise unless you can lock in these prices, which is difficult for large buyers in need of 15-20 years agreements. Third, there has been and still is a large group of price agnostic buyers willing to purchase PPAs at rates well above spot and forward power prices. This segment is likely expanding, with a notable example being the owners of generative AI server farms. These servers consume approximately 4 to 20 times more electricity than traditional cloud servers, and demand forecasts keep being revised higher at a very rapid pace. Finally, if PPA prices fall to levels that are not economically viable, governmental intervention may become necessary to achieve specific climate goals. This approach has been and continues to be a key factor in the development of for example offshore wind projects.

All in all, although we and the market were taken by surprise by the sharp fall in power prices in January, we believe this development creates interesting opportunities on both the long and short side and we see several interesting ways to profit.

- Portföljförvaltare och grundare av fonden Coeli Renewable Opportunities.

- Mer än 15 års erfarenhet av investeringar från både publika och private equity-sidan.

- Förvaltat fonden Coeli Energy Transition sedan 2019.

- Spenderade sex år på Horizon Asset i London, en marknadsneutral hedgefond.

- Började arbeta tillsammans med Vidar Kalvoy 2012.

- Fem år inom Private Equity på Morgan Stanley.

- Startade sin investeringskarriär inom tekniksektorn på Sweden Robur i Stockholm 2006.

- Utbildad Civilingenjör från Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan.

- Portföljförvaltare och grundare av Coeli Renewable Opportunities-fonden.

- Förvaltat aktier inom energisektorn sedan 2006 och har mer än 20 års erfarenhet från portföljförvaltning och aktieanalys.

- Förvaltat fonden Coeli Energy Transition sedan 2019.

- Ansvarig för energiinvesteringarna på Horizon Asset i London under 9 år, en marknadsneutral hedgefond.

- Erfarenhet från energiinvesteringar på MKM Longboat i London och aktieanalys inom teknologisektorn i Frankfurt och Oslo.

- MBA från IESE i Barcelona och Civilekonom från Norges Handelshögskola.

- Innan han började arbeta inom finans var han löjtnant i norska marinen.

VIKTIG INFORMATION. Denna information är avsedd som marknadsföring. Fondens prospekt, faktablad och årsberättelse finns att tillgå på coeli.se och rekommenderas att läsas innan beslut att investera i den aktuella fonden. Prospektet och årsberättelsen finns på engelska och fondens faktablad finns bland annat på svenska och engelska. En sammanfattning av dina rättigheter som investerare i fonden finns tillgängligt på https://coeli.se/finansiell-och-legal-information/.

Historisk avkastning är ingen garanti för framtida avkastning. En investering i fonder kan både öka och minska i värde. Det är inte säkert att du får tillbaka det investerade kapitalet.